You Acquired Their Assets, But Did You Get Their Copyrights?

The legal equivalent of this—

—is trying to assert rights you only think you have. You cock your arm back, ready to throw your rights accurately through your adversary’s defenses, but the ball isn’t there anymore. Where did they go? You never really had them at all.

It might seem odd that you could get to the point of filing a lawsuit without really being able to establish the most foundational aspect of your case, but in copyright law, this isn’t uncommon. There are a few reasons for this:

- First, unlike patents and registered trademarks (and realty), is no registry of who owns what copyrights.1And even in realty, mistakes happen. That’s why there’s title insurance. Indeed, there are copyrights out there whose owners we have no idea about.2These are known as “orphan works.”

- Second, there are certain formalities for transferring copyright, which aren’t always complied with, so sometimes the parties think they have transferred a copyright but haven’t really.

- Third, there are just so many copyrights. It’s impossible to keep track of them all.

- Fourth, copyright law just isn’t very intuitive. What makes sense in everyday experience often doesn’t make sense in copyright law. For example, if you hire a developer to make software for you, then you own the copyright in the software code. But you hired an outside firm to do that, the outside firm will own the copyright, and you’ll have to get the firm to transfer to copyright to you—which you might not think to do because it doesn’t make intuitive sense.

- Fifth, paper trials are usually the only way to prove copyright ownership, but they grow cold, get disrupted or hopelessly tangled.

But, hey, at least if lawyers are involved, nothing can go wrong, right? Ummmm….

Did You Buy What You Thought You Were Buying?

Several years ago, Siemens AG spun off its water technologies business into a new company. Siemens assigned everything related to its water technologies, except “IP,” which was defined as “trademarks and their applications3What, no love for trademark registrations?, domains4I.e., domain names. and any other intellectual property rights.” But that was only because Siemens was being very careful about what intellectual property it was parting with. It didn’t want to give away anything it still needed for itself.

So, in the following four sections, Siemens transferred to the new business (1) “patents and trademarks,” (2) “know-how,” (3) “software,” and“ (4) ”domains. The agreement did not explicitly discuss transferring copyrights, but I think it’s safe to assume that the “software” section was written so that copyright in the software was transferred (because otherwise the software would be illegal for the new company to use).

This was a problem, though, because the new company, now called Equova Water Technologies, is now suing a despised rival for infringing the copyright in Equova’s product brochures, manuals and presentations. This rival, now called “M.W. Watermark,” was founded by a former Siemens employee and originally made replacement parts for Siemens’ water equipment. That’s legal, of course, but it’s extremely annoying to the manufacturer, which would prefer to monopolize replacement parts. When Equova announced that it was discontinuing a line of products5Sludge dryers. It removes water from industrial waste., Watermark jumped in with its own line of products, using a somewhat, kinda-sorta similar product name.6Equova’s name was J-MATE. Watermark’s allegedly infringing name is DryMate. The MATE element is doing a lot of lifting.

It didn’t help that this was the second dust-up between the two parties, and last time Watermark had to back down a lot—to the point where it was forced to enter into a consent injunction preventing it from using MATE for itself and its products.7Which is why Watermark is now called Watermark, and not “J-Parts,” a name that wasn’t going to win them any friends over at Siemens/Equova.

The Wonderful World of Sludge Dryers

This time, however, Equova wasn’t just bringing trademark claims. Oh no. It was bringing copyright claims, on such exciting titles as “How Does a Filter Press Work?”, “J-Press Liquids-Solids Filtration Equipment and Separation Equipment,” and “J-Press Filter Press 630 MM Owner’s Manual.”8I know I’m having a little fun with this, but the copyrights in these quotidian documents are quite real and are as enforceable as copyrights in novels, films, songs and paintings. It goes to show that the subject matter protected by copyright is extremely broad and extends far beyond “creative works.”

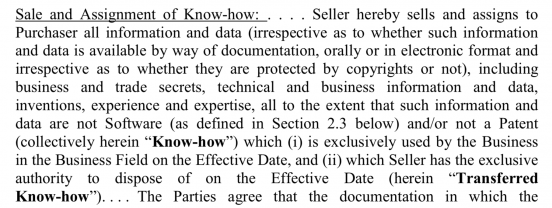

When Watermark asked Equova to explain how it owns the copyrights in the brochures, manuals and presentations at issue, Equova pointed to the “know-how” provision in that original assignment agreement. In pertinent part, it goes like this:

Does assigning “all information and data” also assign copyrights? A copyright lawyer would say, “Of course not.” There is no copyright in mere information and data. Copyright doesn’t protect facts. It might protect the way facts are arranged or otherwise expressed, but not the facts themselves.

But this isn’t really a question of copyright, but a question of contract interpretation. Would this provision make you think that the parties intended for Siemens to assign the copyrights to the new company, bearing in mind that the companies (sophisticated as they were) were not copyright lawyers?

The trial court thought the answer was clear: copyrights were not transferred. No reasonable person could interpret this language that way. But on appeal, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals thought that a reasonable person might interpret the language to include the assignment of copyrights. It pointed to the word assign, which is defined by the leading legal dictionary as meaning “to convey in full; to transfer (rights or property).” So, while the parties aren’t necessarily conversant in the basics of copyright law, they might be very familiar with legal dictionaries, I guess. It also thought that “information” could be construed broadly to include not just facts but also “a wide variety of assets.”9The court does not cite to any authority for this, nor does it explain further. The Sixth Circuit also makes much of the stray mention of “copyright,” which it thinks suggests that any copyright might be transferred along with the data and information.

In short, the Sixth Circuit held, it’ll be up to a jury (standing in for the “reasonable person” in the formulation above) to figure out whether this provision transferred copyrights along with the data and information.

Schrödinger’s Copyright

So, that’s a victory for Equova, right? The parties clearly meant to transfer the copyrights to the new company, because the deal doesn’t make sense otherwise.

But take a step back. Right now, nobody knows who owns the copyrights. And we won’t know until a jury makes a determination.10More precisely, we don’t know who OWNED the copyrights when Equova sued, which is the legally relevant point in time. Surely, by now, Siemens and Equova have rectified the oversight. That’s not a successful outcome. In an acquisition agreement, the point is to be absolutely clear about what assets are being transferred. Yet you cannot tell from the agreement whether the copyrights have been transferred.

Now imagine that Equova’s assets get split up and sold, which is a fairly common occurrence. And imagine if enough time passes that no one remembers the original deal well enough to testify about it. Did we intend to transfer those copyrights? It makes sense, but no one hear actually remembers… Equova’s successor in interest calls Siemens over and over, begging for an assignment document, but Siemens has moved on and has better things to do….

To be fair to the drafters, these particular copyrights aren’t crucial to the deal. At least they aren’t important revenue-generating assets, right? From the perspective of the deal, the worst that would happen is the new company would have to re-create its manuals and presentations. And, if worse came to worse, you can just ask Siemens to execute an assignment.11If you’re wondering, if Siemens has since rectified the problem in this way, then Equova could drop the copyright claims in this case and file a new suit. That might’ve been faster than appealing, but there were other, more important issues on appeal. That a despised rival would copy them for their own purposes didn’t enter anyone’s minds. Also, copyrights are nerdy and weird, and M&A lawyers don’t like to get that icky stuff on them.

Still, it wouldn’t have been hard to add a comprehensive “copyrights” section to the agreement. There are so many copyrights that the dealmakers can’t be cognizant of them all—or predict which ones will become significant in the future. Better to have a provision that transfers all of copyrights relevant not only to the “technology” or “software,” but also the products. Product manuals, educational videos, drawings, photographs, and so forth took company resources to make: you might as well own their copyrights so you can keep using them in the future, you know?

Thanks for reading!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | And even in realty, mistakes happen. That’s why there’s title insurance. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | These are known as “orphan works.” |

| ↑3 | What, no love for trademark registrations? |

| ↑4 | I.e., domain names. |

| ↑5 | Sludge dryers. It removes water from industrial waste. |

| ↑6 | Equova’s name was J-MATE. Watermark’s allegedly infringing name is DryMate. The MATE element is doing a lot of lifting. |

| ↑7 | Which is why Watermark is now called Watermark, and not “J-Parts,” a name that wasn’t going to win them any friends over at Siemens/Equova. |

| ↑8 | I know I’m having a little fun with this, but the copyrights in these quotidian documents are quite real and are as enforceable as copyrights in novels, films, songs and paintings. It goes to show that the subject matter protected by copyright is extremely broad and extends far beyond “creative works.” |

| ↑9 | The court does not cite to any authority for this, nor does it explain further. |

| ↑10 | More precisely, we don’t know who OWNED the copyrights when Equova sued, which is the legally relevant point in time. Surely, by now, Siemens and Equova have rectified the oversight. |

| ↑11 | If you’re wondering, if Siemens has since rectified the problem in this way, then Equova could drop the copyright claims in this case and file a new suit. That might’ve been faster than appealing, but there were other, more important issues on appeal. |