Last week I read a smart post about some of the shortcomings of the now 20-day-old California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), and how it may not cover downstream data resellers in any kind of an effective way. I encourage anyone working in the data protection space to read it.

In the post, the author described the now “ubiquitous” disclosures “prominently displayed” on the homepages of companies stating that they may “sell” information (as that term is broadly defined in the CCPA) and giving Californians the chance to opt out of such sale of their information. These notices are a requirement under the CCPA. Specifically, Section 1798.135(a) states that business that sell the information of Californians and are otherwise subject to the CCPA must:

Provide a clear and conspicuous link on the business’s Internet homepage, titled “Do Not Sell My Personal Information,” to an Internet Web page that enables a consumer, or a person authorized by the consumer, to opt-out of the sale of the consumer’s personal information.

From the examples in the post, it seems that many of the major companies in America have gotten on board with this Do Not Sell My Personal Information (DNSMPI) link. But the average consumer viewing this sites would have absolutely no idea. The part of the statute that they seemed to have overlooked is the part that says those links must be “conspicuous.”

The author lists a number of companies that have recently added DNSMPI links. A friend in California (who shall remain nameless for privacy purposes) reviewed the homepages of each of these sites for me, in case the opt-out link had been geo-fenced in some way and I just wasn’t seeing it outside of California. In every single case, the DNSMPI link is buried on the footer, generally in the same font as everything else, or in certain cases smaller font. You can find it somewhere under the “Legal Notices” and “Contact Us” buttons. Here are a couple examples

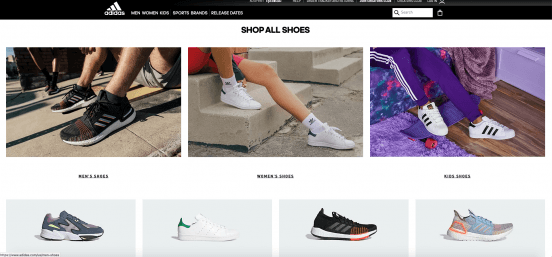

Adidas: Homepage “Above the Fold”

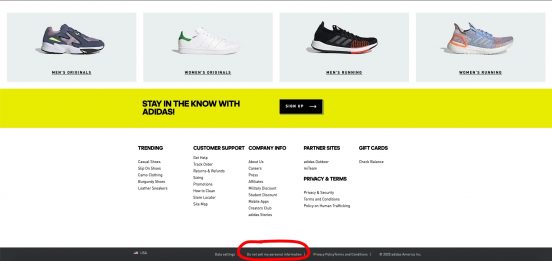

Adidas: Homepage “Below the Fold”

You can’t see it at all when you first go to the homepage on any normal size monitor. (Mine is a 24”).

One more example. I had to scroll 4 times down the Colgate-Palmolive homepage before I got to this footer:

I reviewed the homepages, as seen by a California resident, of these two companies, plus Disney, GM, McDonalds, Ebay, and Uber. Every one of them had the DNSMPI link buried in the footer.

The statute says that these links must be “clear and conspicuous.” There are a number of ambiguities in the CCPA, but this is not one of them. Nor is “conspicuous” an unfamiliar term to lawyers in America. For example, the term is defined in the Uniform Commercial Code as follows:

with reference to a term, means so written, displayed, or presented that a reasonable person against which it is to operate ought to have noticed it. Whether a term is “conspicuous” or not is a decision for the court. Conspicuous terms include the following: (A) a heading in capitals equal to or greater in size than the surrounding text, or in contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same or lesser size; and (B) language in the body of a record or display in larger type than the surrounding text, or in contrasting type, font, or color to the surrounding text of the same size, or set off from surrounding text of the same size by symbols or other marks that call attention to the language.

IT’S THE REASON THAT THE DISCLAIMERS OF WARRANTY WE DRAFT ARE IN ALL CAPS. A reasonable person visiting the Adidas website is interested in the “SHOP ALL SHOES” link that is “above the fold” on the homepage. They are not as likely to be interested in the Company Info and Partner Site links at the bottom. It’s possible that they will scroll down if they want to join Adidas’ mailing list, but is it likely that they will see the greyish small font on the black background below as anything other than a site border? Dear readers, I am afraid that this was the point. Data deletion processes can be quite complicated to establish and onerous to maintain. It is understandable and foreseeable that companies would rather not have consumers clicking on a DNSMPI link at all. The drafters of the CCPA knew this, of course. It’s why the word “conspicuous” shows up in the statute.

The CCPA is only 20 days old and it has a lot of work to do. The Attorney General of California has said that he won’t enforce the law until July when the rules are finalized, but that he will prosecute ongoing violations going back to January 1. But whether it’s now or whether it’s in July, my hope is that the AG’s office makes it quite clear to companies needing to comply with the statute that “conspicuous” means what we know it means. Because if it doesn’t, then what are we supposed to think of the other far less clear provisions in the law? The need for the CCPA to be effective and enforced is becoming alarmingly clear from a consumer perspective – we learned late last week that ClearView AI has been secretly harvesting all of our public-facing photos and attaching as much personally-identifiable information to them as they can find and selling that information to law enforcement offices all over the country, making it almost impossible in some places to walk down the street anonymously. If CCPA wasn’t meant to stop that, then I’m not sure what the point is of businesses spending thousands of dollars to try to comply.

Clarity and certainty in the rules is ultimately what will benefit businesses the most, even if it means dealing with consumer requests that they don’t want to deal with.

Pro-Tip: Don’t hide your DNSMPI links.