Photograph by Reuben G. Brewer, under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

Hail to the Washington Football Team!

By now you’ve probably heard that the American football team that plays in the Washington D.C. area has decided to change its team name from a racist slur to, well, something else. Nobody’s not sure yet. The Washington football team hasn’t decided. There are fairly well-substantiated rumors that this delay is the result of a “trademark dispute.” And there’s reasonable speculation that this trademark dispute has to do with one Martin McCaulay. He’s been treated in the media as something of a trickster folk hero for applying to federally register a number of likely team names, then holding them hostage.

This is popular because hardly anyone likes the Washington football team. Yes, the racist slur has a lot do with it. But perhaps even more important is that the team’s owner, “Chainsaw” Dan Snyder, is both high-profile and aggressively unlikable. (Here is how he earned the “Chainsaw” moniker.)

Sports Team Names Are Different in the U.S.

If you’re not an American or Canadian, this might seem just so much meaningless drama. But unlike in other countries, American and Canadian sports teams (nearly always) choose their own team names. And the team name is crucial to the teams sports and commercial identities. The idea of a sports team lacking a team name is unthinkable to an American or Canadian.1The exception that proves the rule is professional soccer teams in the U.S., which mostly have adopted European-style monikers, e.g., Real Salt Lake. But that’s just a sign of how popular European and Mexican soccer leagues are in the U.S. Attempts to name soccer teams American style just sounds inauthentic. By contrast, nicknames of sports teams elsewhere tend to develop organically from the fan base.2The oldest of U.S. team names developed this way, too. E.g., the (now) Arizona Cardinals got its name from the color of the cast-off University of Chicago uniforms they used to wear. The Green Bay packers got its name from its original sponsor, a packing company.

Snyder swore for years and years that he would never abandon the racist slur. He grew up a fan of the team and seemed genuinely attached to the name emotionally. But then, suddenly, he changed his mind. More precisely, events overtook him, and changing the name suddenly looked like a good idea, and one that had to be done quickly.3In particular, his team’s main sponsors demanded the change. There was no time to give any thought about what name should replace the racist slur, just that the racist slur had to go.

If you’ve ever been involved in re-branding—and most trademark lawyers have—none of this is very surprising. Changing a brand can be very disruptive to business, maybe even fatal. To be done correctly, re-branding must be approached very carefully, very thoughtfully and very gradually. When I heard that the Washington football team was just going to call itself the “Washington Football Team” for the time being, I thought that was the correct decision under the circumstances, though the decision was widely derided. It’s going to be your name for a long, long time. You might as well get it right.

Mr. McCaulay’s Trademark Applications and Registration

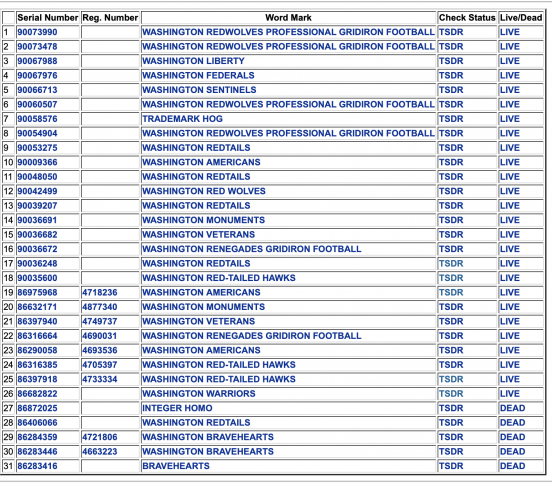

Mr. McCaulay has applied to register, and in some cases, has obtained registrations for a number of Washington football-related trademarks:

This list shows U.S. trademark applications and registrations held by Mr. McCaulay personally.

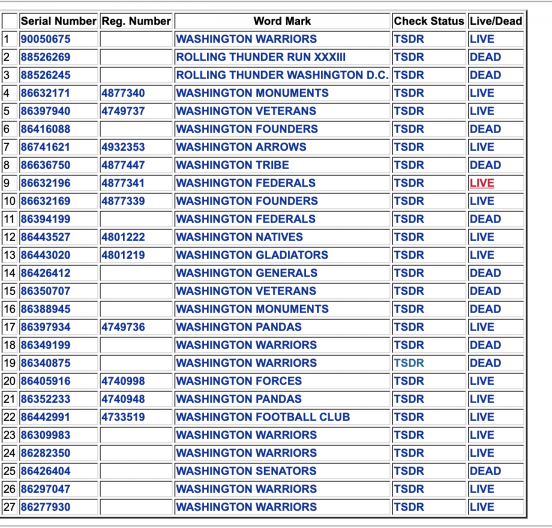

This list shows U.S. trademark applications and registered held through an entity I believe is controlled by Mr. McCaulay.

Most, but not all, of these he filed since July 4, soon after it became clear that the Washington football team was going to change its team name. He has, for the most part, filed the new ones as “intent-to-use” (or “ITU”), which means that he has a good-faith intent to use them in commerce for the goods and services listed on the application. The goods and services in these new applications have been “entertainment in the nature of football games,” along with some secondary uses for apparel and equipment.

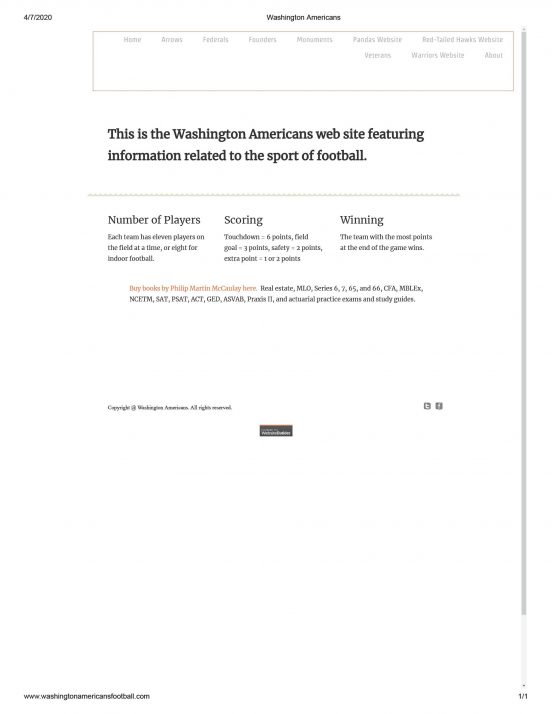

The older (registered) ones are for “providing a website featuring information relating to the sport of football.” He would create almost meaningless websites that told you extremely basic information about American football, like how many points at touchdown is worth. And the stunning fact that the team with the most points at the end of the game is the winner.

The specimen of use for one of Mr. McCaulay’s trademark applications.

One presumes that Mr. McCaulay intends to profit from this “hobby,” though he’s given mixed signals about that. But it’s the only thing that makes sense. He says he’s spent over $20,000 in filing fees on this hobby, and he describes it as a “high-risk investment.”

If so, it shouldn’t count on a big payday, or even any profit.

Trademark Law Is Different in the U.S.

In the United States, there is only one source of trademark rights: use in commerce. Not the government. This means:

- A trademark registration doesn’t by itself create a valid and enforceable trademark.

- A trademark can be valid and enforceable without a registration.

There are lots of good reasons to register marks, but registration isn’t strictly necessary—and it doesn’t substitute for actual use in commerce.

Trademarks represent consumers’ view of the quality of the goods and services sold and promoted under the trademark. You can’t fake that, and you can’t conjure it out of thin air. Not even the federal government can do that.4In contrast to the U.S.’s crazy, unfair system for registering copyrights, I believe the U.S. is correct to insist on use in commerce.

The Registrations: Are These Really Uses in Commerce?

Let’s start with Mr. McCaulay’s (older) registrations. Mr. McCaulay knows that you can’t just “reserve” a trademark by applying for it. You have to use it. So he created these intensely lame websites, like this one. Note how Mr. McCaulay advertises his own books at the bottom. I assume that’s meant to make this use of WASHINGTON MONUMENTS a commercial one.

This “use” is good enough to fool the trademark examiner. Examiners are just looking for specimens that show, on their face, that the mark is being used in commerce. They aren’t obligated to “look behind” the proffered specimen to make sure.

But it isn’t going to be good enough to prove WASHINGTON MONUMENTS (or whatever) is a valid mark. The registration creates a presumption of validity, but that presumption can be rebutted. If Mr. McCaulay were to sue the Washington football team over one of these marks, the Washington football team would absolutely learn all about his commercial use of the trademark, if any.

Did You Know a Touchdown Is Worth Six Points in American Football?

If it’s just this lame webpage, I think the court will hold he never had a valid trademark, despite the registration. It isn’t a “use in commerce.” Mr. McCaulay isn’t selling or offering to sell anything. Yes, he’s “advertising” his books, but his putative trademarks aren’t for books. They’re for providing information about football. Put another way, he’s not using WASHINGTON MONUMENTS in a way that would make a consumer associate that term with a quality source of football information. It’s such a de minimis use of the mark that it’s the functional equivalent of reserving the mark.

What’s the point, then, of the registration? The presumption of validity really is valuable! Ordinarily, the burden is on you to prove up the validity of your trademark, and that is often a difficult and expensive task. With the registration, you put the burden on the defendant to prove your trademark isn’t valid. And, nine times out of ten, the defendant sees enough commercial use that it isn’t worth fighting.

The ITU Applications: Is This Really a Bona Fide Intent to Use in Commerce?

The newer applications are “intent-to-use” (“ITU”) applications. Remember how I said you can’t the U.S. trademark registration system to “reserve” a trademark? ITU applications are kind of an exception—but with meaningful limitations designed to prevent abuse.

The key advantage conferred by ITU application is you are deemed to have started using the trademark on the date you filed the ITU application, even though you don’t really start using the mark until later. That’s contrary to the main thrust of U.S. trademark law (and was, naturally, the result of a need to bring U.S. law closer into conformance with other countries’ trademark laws). So there are two major limitations to this type of application:

- You must have an actual intent to use the mark for the goods and services on the application, at the time you file.

- You must actually start using the mark in commerce within a set period of time, or else your application goes abandoned.

Now, you might have noticed that Mr. McCaulay’s applications aren’t just for providing information about football. They’re for actual football games (er, “entertainment in the nature of football games”). So, how does he justify claiming he has a honest-to-goodness intent to use, say, WASHINGTON REDTAILS, in connection with football games? He’s hardly in a position to form a professional football team.5For our European friends: There aren’t really lower professional football leagues, the way soccer has lower divisions or baseball has the minor leagues. Instead, American football teams rely almost entirely on college football for talent and to serve as a kind of amateur proving ground for players. So if you’re thinking he could try to form the equivalent of a second-division Scottish soccer team, that’s not really an option here.

Flagging Football

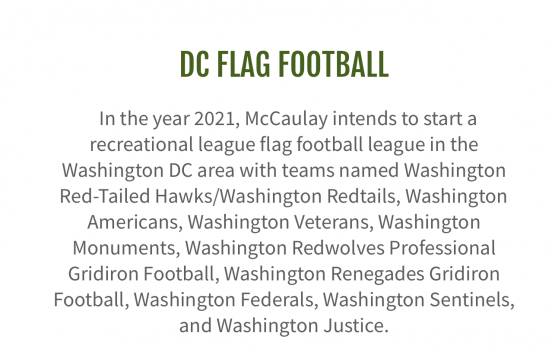

Get ready for some next-level thinking. Nobody said it had to be regular tackle football. What if it were… flag football?!6Flag football is a type of American football that substitutes grabbing “flags” from the ball-carrier’s belt for tackling. It’s a lot cheaper and safer to play, but not as fun.

That’s right. Mr. McCaulay is going to set up a recreational flag football league, comprised of teams that happen to have the same names as what he’s registered or applied for. Brilliant!

A screenshot from a webpage for the “Washington Redtails,” one of the team names Mr. McCaulay is trying to lay claim to. This shows his plans for a flag-football league in 2021.

Only, no. This reads as more aspirational than intentional. “Bona fide intent” means you have taken “concrete steps” to use the trademark in commerce. It means that you will use the mark in commerce, unless something unexpected happens. While your subjective belief in the efficacy of your plans matters, your word alone won’t be enough. Courts and other tribunals will expect you to have documented these “concrete steps.” Has Mr. McCaulay secured playing fields? Has he secured funding? Purchased equipment? Does he have others “on board”?

For all I know, Mr. McCaulay really has taken “concrete steps” to set up this Washington-area recreational flag-football league. Maybe that’s where some of the $20,000 he’s invested has gone to: buying equipment, putting down deposits on playing fields, and so forth. But I’m not going to bet on it.

Has Mr. McCaulay Made a Big Enough Nuisance?

In the media, it’s assumed that Mr. McCaulay has the Washington football team cornered. But I’m not convinced.

All the Washington football team would need to do is start using its preferred team name, then dare Mr. McCaulay to sue. Remember, the Washington football team doesn’t need to wait to get a registration to start using the trademark. That’s preferable, but not necessary. It’d be up to Mr. McClaulay to stop the use. At that point, the Washington football team would be permitted to carefully interrogate Mr. McClaulay’s rights to the trademark. In the case of registrations, the team would need to overcome the presumption of validity, but it’s got the resources to do so. In the case of the applications, it doesn’t even need to do that—Mr. McCaulay isn’t even using the trademarks right now, so he has no rights. As soon as those applications come up for opposition, the football team can attack them then and prevent Mr. McCaulay from ever getting those registrations.

Mr. McCaulay’s only hope is that the Washington football team has such a preference for neatness and tidiness, that it’s willing to pay him to get out of the way. Trademark registrations are so ingrained in the minds of American business that many business folks can’t imagine using a trademark without at least first applying to register it. If you can’t put a serial number with it, it might as well not exist in these folks’ minds.

With all those applications and registrations clogging up the system, any application by the football team would get hung up until Mr. McCaulay’s got resolved. That would take time, and the folks running the Washington football time might lack the patience. Easier, then, to just pay Mr. McCaulay a few bucks to either buy the registration or have him drop his ITU applications.7Note: you can buy use-based trademark applications but not ITU applications. The reasoning is that there isn’t really anything to buy—it’s just a potentiality.

Would the Washington football team be willing to pay him more than $20,000, though?

A New Player Enters the Arena

A parting thought. There’s a third party involved. What appears to be perhaps a youth football league or team—I can’t confirm it—has recently applied to register WASHINGTON WARRIORS for, among other things, playing football games. WASHINGTON WARRIORS is viewed as a leading candidate for the Washington football team’s new name because it’s so anodyne, and because of alliteration, I guess. Well, that, and the fact that Chainsaw Dan Snyder previously applied to register WASHINGTON WARRIORS for an “Arena”-league football team8The now-defunct Arena League played a modified type of indoor tackle American football.

Unlike Mr. McCaulay’s applications, this application is use-based. The applicant claims to have started using WASHINGTON WARRIORS for football games since 2009. If this is true, the applicant—and not the Washington football team or Mr. McCaulay—would gain the exclusive right to use WASHINGTON WARRIORS in connection with football games.

This is so even though the applicant never bothered to register the trademark. Remember, you don’t need a trademark registration to have a valid and enforceable trademark. You just have to use it in commerce.

Use in Commerce (Maybe) Without a Registration

But it’s not that simple. Trademark registration is notice to the United States that you claim those trademark rights. Without a registration, your trademark rights extend only as far as actual consumers might actually encounter the trademark. If your commercial use is obscure, your rights will be limited—and weak.

Mr. McCaulay and the Washington football team will be forgiven if they are a bit skeptical about this application, and not just because of the timing. I can find no independent use of the mark on the Internet. The specimen is a photograph of a black-and-white print-out of a photograph of young football players wearing WASHINGTON WARRIORS gear. The specimen looks real, and there does appear to have been a semi-pro Washington Warriors football team. But I can’t find any activity since about 2015.

Without the benefit of a registration, the applicant will bear the burden of proving use in commerce dating to 2009 (or whenever). If the Washington football team were to adopt WASHINGTON WARRIORS, and the applicant were to sue, the Washington football team could make the applicant work very hard to prove not only use but also that the mark hasn’t been abandoned.

A court might legitimately rule that the WASHINGTON WARRIORS youth football team and co-exist with the WASHINGTON WARRIORS professional football team, even in the Washington D.C. area. The youth football team’s use is weak, and football fans are used to teams sharing the same team name, so they’re unlikely to be confused.

Having said that, the application is still in a much stronger legal position that Mr. McCaulay, would seem to have no rights, whereas the applicant had (and might still have) some weak rights. In that case, selling the mark to the Washington football team for a tidy sum is a real possibility.

Getting it Right

Finally, a note about the Washington football team’s recent application to register WASHINGTON FOOTBALL TEAM. This isn’t as crazy as it sounds. “Football team” is generic, but “Washington” is geographically descriptive. This means that, with enough secondary meaning, Washington could be a source-indicator for football games in the Washington D.C. area. The Washington football team has been playing in and around Washington D.C. for decades, and it has a high national profile. And the team has the resources. So I think the team has a good shot at getting the term registered.

Thanks for reading!

Further Reading (and Viewing)

- I’ve demonstrated what a nerd I am about the history of American football before, in blog post about the Baltimore Ravens’ wingéd shield logo. And again.

- If you’d like to learn more about the process of registering trademarks with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, here’s Tara with a helpful introduction.

- It’s possible that an “opposition” or “cancellation” proceeding (to block issuance of a registration or to knock one out) is in the offing. You can learn more about those types of proceedings here, but bear in mind that at least some of Mr. McCaulay’s registrations are more than five years old.

- Finally, the Washington football team has been in the process of “clearing” its choices for a replacement trademark. That’s smart, actually, even if it’s forced to go with “Washington Football Team” for the time being. The consequences of failing to clear marks is this blog post about a lacrosse company that made it big on Shark Tank.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The exception that proves the rule is professional soccer teams in the U.S., which mostly have adopted European-style monikers, e.g., Real Salt Lake. But that’s just a sign of how popular European and Mexican soccer leagues are in the U.S. Attempts to name soccer teams American style just sounds inauthentic. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The oldest of U.S. team names developed this way, too. E.g., the (now) Arizona Cardinals got its name from the color of the cast-off University of Chicago uniforms they used to wear. The Green Bay packers got its name from its original sponsor, a packing company. |

| ↑3 | In particular, his team’s main sponsors demanded the change. |

| ↑4 | In contrast to the U.S.’s crazy, unfair system for registering copyrights, I believe the U.S. is correct to insist on use in commerce. |

| ↑5 | For our European friends: There aren’t really lower professional football leagues, the way soccer has lower divisions or baseball has the minor leagues. Instead, American football teams rely almost entirely on college football for talent and to serve as a kind of amateur proving ground for players. So if you’re thinking he could try to form the equivalent of a second-division Scottish soccer team, that’s not really an option here. |

| ↑6 | Flag football is a type of American football that substitutes grabbing “flags” from the ball-carrier’s belt for tackling. It’s a lot cheaper and safer to play, but not as fun. |

| ↑7 | Note: you can buy use-based trademark applications but not ITU applications. The reasoning is that there isn’t really anything to buy—it’s just a potentiality. |

| ↑8 | The now-defunct Arena League played a modified type of indoor tackle American football. |